"YOU'RE NOT SUPPOSED TO BE FEEDING ME, YOU KNOW."

The seagull had that certain sort of look on his face that seagulls get from time to time. The sort of look that's comprised mostly of indifference, mixed in no particular order with authoritativeness, a dash of know-it-all bourgeois attitude, a wide-ranging condescension towards life in general, and an overall sense of smugness.

It’s a special sort of combination. A combination that seagulls are nature’s best at exhibiting. One that nearly instantaneously lets you know that whatever it is you’re doing – however it is you’re choosing to exist at that very moment in time – it is not nice, it is not helpful, it is not necessary, it is not important, and it is certainly not a courtesy to anything or anybody.

All of which was fairly coincidental. Because it just so happened that, only moments before, Josie had thought she was being all of those things.

She had innocently thought the seagull looked hungry. And a little lonely, too.

That had been a mistake.

“I said, you’re not supposed to be feeding me.”

The seagull examined the bits of bread Josie had torn off from her sandwich and tossed toward his direction. His head switched from one piece to the next, and then to the next, and then to the next, and then to another before twitching back to the first and then back again to the last.

He was swift. He was efficient. He wasted very little energy in his inspection.

He was as thorough a seagull as Josie had ever seen.

“Oh,” she said. “Sorry. I didn’t know I wasn’t supposed to.” The seagull left footprints in the sand that looked like tiny little arrows, as if to point out each one of her delinquencies. “Sorry about that.”

“There’s a sign,” Mr. Seagull replied.

“I’m sorry?”

“I said there’s a sign. Over there. Right next to the entrance of the beach. Look there.” Mr. Seagull pointed with his wings. The wind tickled his feathers, like keys to a piano.

He didn’t seem to notice, though. “Do you see it? It establishes all the rules for this beach. No dogs. No smoking. No glass bottles. No rough play. No surfing. And no feeding the seagulls.”

Josie turned around. “Oh,” she muttered. “Yeah. Yeah, I see it now.”

Of course, she had seen the sign beforehand.

It had been impossible to miss.

It was big. It was ugly. It had big, ugly letters crudely painted on it. It cast a shadow along the pathway to the beach. It made the sand underneath it wet and chilly and uninviting. It had been laden with misspellings, too.

‘Dogs’ was spelled with ‘z.’

‘Rough’ was spelled with an ‘f.’

‘Seagulls’ was somehow spelled just with the letters ‘c’, ‘g’, ‘l’ and ‘z.’

So she had noticed the sign. It had been a sign worth noticing.

“This is a public place, you know,” Mr. Seagull informed her. “It’s meant for everybody. And the rules on that sign are there to help make sure that everybody can enjoy it, without hindrance to one another. We all give up a little something so that everybody can enjoy this place as much as possible.”

“No, no. I understand that,” Josie said. “I guess I just must have missed it.”

“Has anybody else approached you?”

“Um.”

“Other seagulls. You didn’t feed Brett, did you?

“Brett?”

“Yes, Brett. You’d recognize Brett if you saw him. White feathers, with black and gray highlights. Yellow beak. Little beady eyes. Bit of a smug look to him. He’s a real jerk, that Brett.”

“Oh, no,” she said shaking her head. “No, you were pretty much it.”

“Are you sure about that? Birds of a feather tend to flock together, and all that.”

“No, no other birds. You were it.”

“Well then, I suppose this could have been worse.”

“I guess, yeah.”

“Not much worse, mind you. But no harm, no foul. No pun intended of course.” Mr. Seagull sighed. “What’s your name, young lady?”

“Josie.”

“Well, Rosie. I can see you made an honest mistake. You broke the rules, certainly. Without a doubt. But a mistake nonetheless. So, do you know how we’re going to resolve this matter on this fine afternoon?”

“How?”

“Well, like so. First, you will remain silent about this matter. You will not tell any other human being about what you’ve done here. You will not blog about it, you will not compose any emails to friends or family about it, you will not post upon Facebook about it, and you most certainly will not tweet about it. I, in the meantime, will make sure that no other seagulls find out about your indiscretion here. Which means, I suppose, I and I alone shall have to clean up every single piece of bread you’ve dispensed here. In fact, you best hand over the rest of your sandwich to me, as well as any other food you may have. Just to completely hide the source of the crime. Better safe than sorry, you know.”

“You want the rest of my food?”

“Yes, yes. In fact, the more I think about it, the more it seems absolutely necessary. To protect you, of course.”

“Oh.”

“Please, no reason to thank me.”

“Thank you?”

“You’re welcome. Just please, Rosie. Don’t let it happen again.”

Josie had thought he had looked hungry. And a little lonely, too.

Now she sat in her chair, hungry and alone herself, without her sandwich or the bag of chips she had brought along with it. And she watched Mr. Seagull gobble down each one of her crimes against the community. And when he was finished with that she watched him waddle away with an indifferent look on his face, a look that was mixed with a bit of condescension and a know-it-all attitude, presumably on the lookout for other people who thought they too were being nice and courteous.

And she began to wonder.

Who put that sign up anyway?

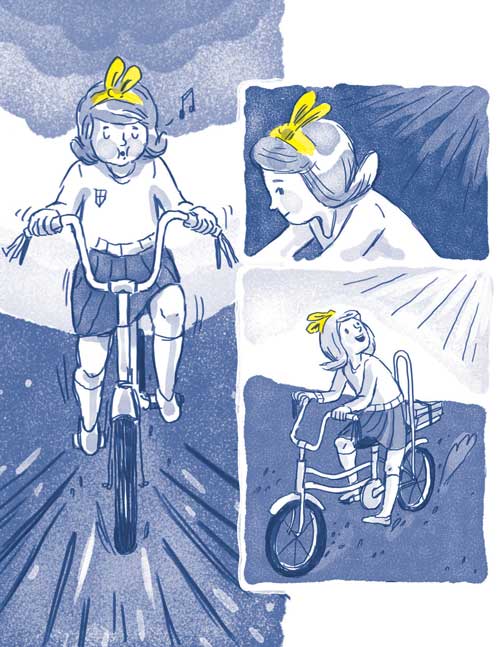

RACHELLE MEYER

Rachelle Meyer graduated with a degree in Studio Art from UT Austin. Her talents have been used to interpret the work of authors such as Dave Eggers, Audrey Niffenegger and Nick Ortner. She now lives in Amsterdam with her English husband, her Dutch son, and her cranky old New York cat.

You can find out more on her website HERE.

“When Sixpenny expressed an interest in receiving animated GIFs as editorial illustrations, the tech nerd in me awoke to the challenge. It felt like an additional thrill to find visual solutions that would work for both the print and online magazines. In particular with this story, I was inspired to movement quite literally when I read the sentence: “The wind tickled his feathers, like keys to a piano.””

DAVID NOVAK

David Novak graduated from Rutgers University with a Masters in City and Regional Planning. He now works in a fairly serious job that’s constantly sending him to strange and mysterious places all across the great state of New Jersey.

“Last summer, my family and I celebrated my mother’s sixtieth birthday by vacationing down in Cape May, New Jersey for a weekend. It was before the busy season, so the beach was nearly deserted except for us and, of course, dozens of seagulls. I began to imagine them as the ones truly in charge of the beach, as the ones who had complete control over it, and used that control to manipulate the rules for their own benefits - and thus, the seeds for my story were planted.”